When Yom Tov falls on a Friday or Thursday/Friday (“three-day Yom Tov”), one is required to prepare an “eruv tavshilin” in order to be permitted to cook on Yom Tov for Shabbat.

The essence of the eruv is to cook a dish[1] — or designate a previously cooked dish — on the day before Yom Tov for the purpose of Shabbat. By preparing this cooked dish, one is essentially starting the preparations for Shabbat, and it thereby becomes permissible to continue those Shabbat preparations on Yom Tov itself.

It is for this reason that we give it the name “eruv,” which means a “blend.” We “blend” the preparations of Shabbat together with the preparations of Yom Tov that we perform on Erev Yom Tov.[2]

The requirement to make an eruv is Rabbinic in nature. According to Torah law, one is permitted to start even the initial cooking for Shabbat on Yom Tov itself without an eruv (this point will be further elaborated below). However, the Chachamim were concerned that this might lead people to think that one may cook on Yom Tov for a weekday too — which in reality is strictly forbidden.[3]

The Chachamim thereforeforbade cooking on Yom Tov for Shabbat without an eruv. In this way, people would reason that if it is forbidden to cook on Yom Tov for Shabbat, then it is certainly forbidden to cook on Yom Tov for a weekday.[4]

Another reason for making an eruv is that when Yom Tov precedes Shabbat, people might serve all their delicacies on Yom Tov and leave nothing special for Shabbat. By requiring an eruv, the Chachamim ensured that people will be particular to reserve something special for Shabbat as well,[5] and will thereby uphold the honor of Shabbat.

As mentioned above, according to Torah law, when Yom Tov immediately precedes Shabbat, one is permitted to cook on Yom Tov for Shabbat. Why is this so? We know that even “melechet ochel nefesh”— work generally required for food preparation, such as kindling a fire or cooking —is only permitted “l’tzorech hayom,”for the needs of Yom Tov itself. Melachah performed for any purpose other than Yom Tov itself — whether for a weekday or for no purpose at all — is forbidden according to Torah law (issur d’Oraita).

Why then is it permitted to cook on Yom Tov for Shabbat? The Gemara lays down two explanations,[6] and the Poskim (halachic authorities) debate which of the two are accepted ashalacha. This debate carries implications for practical halachah, as will be outlined below.

Raba is of the opinion that what makes it permissible mi’d’Oraita (according to Torah law) to cook on Yom Tov for Shabbat is the principle of “הואיל,” which means “since.” The full term for this expression is “הואיל ואי מקלעי ליה אורחים חזי ליה” — if guests were to show up at one’s house on Yom Tov, food that had been cooked on Yom Tov for Shabbat would then have a use on Yom Tov itself. Because of this possibility (“since”), cooking on Yom Tov is considered to have been done l’tzorech hayom, for the needs of the day, even if guests don’t actually come. One need not even expect company; the fact that guests might just “pop in” justifies (on a Torah level only) any cooking that could potentially be used to serve them — by viewing that cooking for the benefit of Yom Tov itself.

Rav Chisda explains differently, maintaining that according to Torah law, “צרכי שבת נעשין ביום טוב — the needs of Shabbat may be performed on Yom Tov.” In other words, cooking on Yom Tov for Shabbat is not akin to cooking for a weekday or for no purpose at all; it is equivalent to cooking on Yom Tov for Yom Tov itself. Rashi explains that the kedushah (sanctity) of Yom Tov is, to a certain extent, like the kedushah of Shabbat, for Yom Tov is also referred to as Shabbat. Therefore, just as the Torah permits melechet ochel nefesh for Yom Tov itself, it also permits doing so for the purposes of Shabbat.

These two principles of “הואיל” and “צרכי שבת נעשין ביום טוב” only permit cooking on Yom Tov for Shabbat on a d’Oraita level only. On a Rabbinic level(mi’d’Rabbanan), however, the prohibition remains unless one prepares an eruv tavshilin, as explained above.

It is important to understand that because the eruv itself is Rabbinic in nature, on its own it does not carry the ability to permit cooking on Yom Tov in circumstances that would otherwise be prohibited mi’d’Oraita. The sole power of the eruv is to lift a Rabbinic prohibition against cooking on Yom Tov for the sake of Shabbat. Therefore, when neither of the two aforementioned principles are applicable, cooking for Shabbat would remain Biblically prohibited, and the eruv tavshilin would obviously not have the ability to override the Biblical issur[7] and permit cooking solely for the sake of Shabbat.

Is there a situation in which it would be Biblically prohibitedto cook on Yom Tov for Shabbat? The answer depends on whether we follow the opinion of Raba or Rav Chisda.

Raba’s logic of “הואיל”, is applicable only as long as the food prepared on Yom Tov could be used to serve potential guests during Yom Tov. However, if one were to start cooking right before the end of Yom Tov, just before Shabbat enters, there would not be sufficient time for the food to finish cooking and be served to guests. In this case, it would be impossible to consider this cooking for Yom Tov itself, and there would no longer be any justification for that cooking. Consequently, even if one had made an eruv tavshilin, it would remain Biblically prohibited to cook for Shabbat.

According to Rav Chisda’s opinion on the, it would be permissible to rely on the eruv even right at the end of Yom Tov. Because Rav Chisda maintains that צרכי שבת נעשים ביום טוב, one may cook for Shabbat itself irrespective of one’s needs for Yom Tov.

Whose opinion do we accept as halachah, that of Rav Chisda or Rava? The Chafetz Chaim, z”l, brings a lengthy discussion in the Biur Halachah[8] summarizing the debate among the Poskim.

The Chafetz Chaim concludes that one must initially try to cook all the Shabbat dishes well in advance, to satisfy the opinions that rely on the principle of הואיל. If, however, one forgot to cook early in the day, or a need arose to cook something for Shabbat in the last minute, the Biur Halachah says that one may rely on the opinions that accept the principle of “צרכי שבת נעשים ביום טוב.”

However, the Chafetz Chaim points out that when the first day of Yom Tov occurs on a Friday, one must be doubly careful to cook everything early in the day, as this situation pertains an issur d’Oraita. When the first day of Yom Tov occurs on a Thursday, and the second day is on a Friday, the eruv only permits cooking on Friday (the second day of Yom Tov) for the sake of Shabbat, but not from Thursday (the first day of Yom Tov).[9] As the second day of Yom Tov is only Rabbinic in nature, the question is of lesser severity, and there are stronger grounds to be lenient regarding cooking for Shabbat.

In any event, lekatchilla (ideally) one should not leave any Shabbat preparations until the last minute. For this reason, some communities maintained the custom of accepting Shabbat early when Yom Tov immediately preceded Shabbat to ensure that all Shabbat preparations would be performed early enough in the day.

One last tidbit. The Or L’Tzion gives good advice for a person who forgot to cook for Shabbat until close to the end of Yom Tov.[10] We will introduce another concept called “ribuy b’shiurin,” literally translated as “increasing in measure.” This refers to someone who is cooking[11] for the needs of Yom Tov but adds into the pot extra food that is not needed for Yom Tov — before putting it on the fire. This is permitted on Yom Tov since one is doing the cooking that is not needed for Yom Tov with the same single act that is anyway necessary for Yom Tov — with no additional tircha (effort).[12]

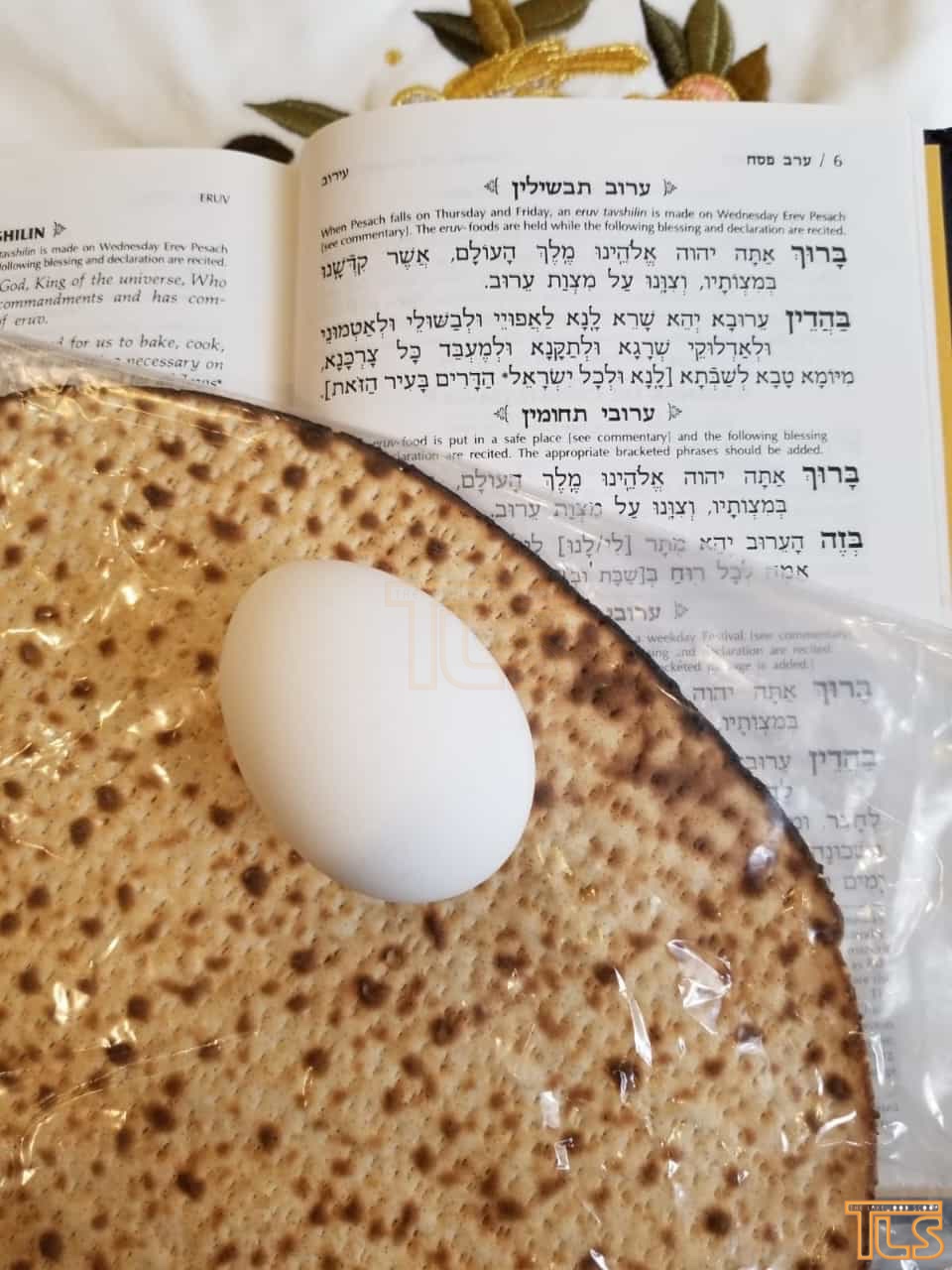

That being the case, says Chacham Ben Tzion Abba Shaul, a person who is delayed in cooking for Shabbat until close to the end of Yom Tov should add something to the pot that cooks quickly — such as an egg — before placing the pot of food on the fire. The egg is considered as having been cooked for Yom Tov itself (even if one does not actually plan on eating the egg on Yom Tov) because of the concept of הואיל. Subsequently, everything else in the pot is considered a “ribuy b’shiurin,” an “increase in measure” in addition to the egg. All the contents of the pot are thereby permissible according to Torah law, and with the eruv, they are Rabbinically permissible as well.

However, it should be mentioned that several Poskim do not consider this to be ribuy b’shiurin (see note).[13] According to those opinions, the sole leniency to cook for Shabbat late in the day is to rely on the Poskim who endorse the opinion of Rav Chisdathat “צרכי שבת נעשין ביום טוב — the needs of Shabbat may be performed on Yom Tov.”

[1] כפי עיקר הדין דרק תבשיל מעכב, אבל לכתחי’ עושין אותו גם בפת (סי’ תקכ”ז סעי’ ב’).

[2] ראב”ד רפ”ו מהל’ שביתת יו”ט, ועי’ שם ברמב”ם טעם אחר.

[3] ואפי’ למ”ד דאמרינן הואיל, אכתי איכא איסור דרבנן לבשל לצורך חול וגזרו אטו זה משום שדברי סופרים צריכים חיזוק (מלחמות ה’ פסחים מו:), אבל לצורך שבת שהוא כשעת הדחק היו מתירים לבשל לכתחילה מטעם הואיל אם לא משום אטו חול (בעה”מ שם). כ”כ בתוספות רעק”א ריש פ”ב דביצה.

[4] טעמו של רב אשי ריש פרק ב’ דביצה שהוא עיקר (עי’ ב”י סי’ תקכ”ז סעי’ י”ד ושעה”צ אות ס”ו).

[5] טעמו של רבא שם, שגם הובא בקצת פוסקים.

[6] פסחים שם.

[7] פסחים שם “ומשום עירובי תבשילין שרינן איסורא דאורייתא?”

[8] ריש סימן תקכ”ז.

[9] ש”ע סעי’ י”ג, עיי”ש הטעם.

[10] ח”ג פרק כ”ב שאלה ג’.

[11] לאו דוקא בישול, דגם שייך במלאכות אחרות כשנעשים בחד טירחא.

[12] עיין סעי’ כ”א, ועיקרו בסימן ק”ג.

[13] כיון שאין התוספת ראוי ליום טוב כמו העיקר. עי’ אחיעזר ח”ג סי’ ס”ה אות ח’ ואג”מ או”ח ח”ה סי’ ל”ה. לעומת זאת עי’ ארחות שבת ח”ג בירורי הלכה סי’ ט’ אות י”ח שכתב דבמאמ”ר ונה”ש סי’ רמ”ז מבואר דלא ס”ל הך סברא. וע”ע בספר יו”ט כהלכתו פ”א הע’ 119, פ”ו הערה 27, ופרק י”ג הערה 100 מו”מ בזה ועוד מראה מקומות.